You see what is, where most people see what they expect. John Steinbeck

To wish was to hope, and to hope was to expect. Jane Austen

You said we cannot sail through, how were you so sure? Mehek Bassi

Our brightest blazes of gladness are commonly kindled by unexpected sparks. Samuel Johnson

Peace begins when expectation ends. Sri Chinmoy

There is no passion to be found playing small – in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living. Nelson Mandela

You can devise all the plans in the world, but if you don’t welcome spontaneity; you will just disappoint yourself. Abigail Biddinger

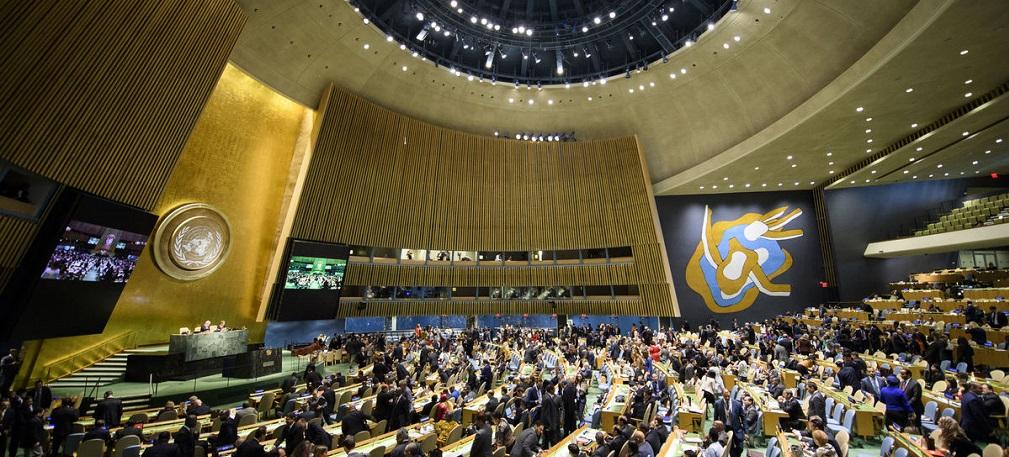

As many of you know, the past two UN weeks were devoted to the High Level Political Forum (HLPF), a monumental effort by the Economic and Social Council to clarify the expectations of states regarding their commitments to the 2030 Development Agenda and to assess the SDG-related performance of states through a process of Voluntary National Reviews.

This HLPF represents, in essence, the half-way point in a 15 year commitment to sustainable development made in 2015 to shift the direction of a global community in positive ways, but one which has actually seen many core Sustainable Development (SDG) commitments experience course reversals. Among others, we are not on track to reduce poverty, address food insecurity, eliminate our fossil fuel dependences, end government corruption or build the durable partnerships needed to bring the health and other material circumstances of global citizens up to even minimum standards in this polarized and unequal world.

Given these and other SDG setbacks, those which the pandemic did not help but also did not cause, one would have been forgiven for assuming that this HLPF would be characterized by the kinds of energy and passion largely absent fronm diplomatic discourse. If there was ever a time to step out of line, to show both urgency and flexibility in terms of how we define the times and our responsibilities to those times, to inspire as well as deliberate, to reassure as well as to demur, this would have seemed to be it.

And we did get some of that, including in the plenary session on ocean health and in “side events” such as one on “water and climate,” another on “invisible” older women, and a third on the sustainability role of local and regional governments, all of which got us closer to clarifying the urgency of the moment and showcasing a bit of the determination needed to overcome challenges, in part due to the active presence in these meetings of issue-relevant NGOs. And yet, as the conference rooms filled up and the ministers uttered their statements, we could well regret that the polar ice caps continue to melt into the sea, children wait in vain for another meal, our freshwater reserves continue to evaporate or succumb to plastic pollution, and we continue to put pressure on what remains of life-saving reserves by doubling down on water sucking agricultural and meat producing practices, as well as on automobiles which represent a double-whammy of massive water (in production) and fossil fuel uses.

In this and other UN settings, it is fair to ask if what we propose for state and non-state action is possibly sufficient to avert levels of looming catastrophe for which, as with the current pandemic, we remain largely unprepared.

Stepping back for a moment, I was reminded this week of a position which has long guided my own thinking – that how was assess is largely a function of what we expect – that multiple people can look at and describe the very same situation and yet assess it differently based on their own expectation of performance. Indeed, around the UN as elsewhere, much of the difference in how we identify and evalauatae the performance of this system is a function of what we have been led to expect or allowed ourselves to expect.

And, I must say expectation levels seem to be headed south as quickly as levels of ocean health. Responses to some of my own frustrations about UN progress on sustainable development or the maintenance of international peace and security is some version of “well, what did you expect?” The flaws in this response, to my mind at least, are obvious in an institution which seeks on the one hand to raise expectations for multilateral engagement while simultaneously dampening them with reminders that, well, it’s the governments that determine objectives and outcomes and the rest of us can do little more than make our case and hope that some other than the usual suspects is actually listening to what we say.

Another flaw in this complex and often-troubling scenario is the assumptions that expectations are what we have of others, that our role in this drama is largely a passive one, waiting to see if persons or institutions can deliver on what are often inflexible and even fantastical assumptions about how “others” should behave, how the world “should” work, expectations so often disconnected from reality, so often insufficiently flexible to circumstance but also insufficiently engaged with the people and/or institutions to which the expectations are directed.

I must say that most of the quotations I unearthed for this piece (and didn’t include) failed both the flexibility and engagement tests. One after another cautioned against having any expectations in the first place, not as a result of some Buddhist epiphany but so one could avoid “disappointment.” As with so much else in life, the choice to recalibrate these dubious assumptions, to refine our expectations such that they remain both flexible and engaged was difficult to find. That we should be willing to see what is actually present, to refrain from predetermined notions of what “ought to be,” notions seemingly also designed to limit our own participation, is a curse which we have the ability and the obligation to curb.

Where this HLPF was concerned, it was a struggle for some not to give in either to a passive cynicism or a deep disappointment that, yet again, conclusions were not sufficiently relevant to the urgency of the times and young people were no closer to securing a world they can live with. After “consensus” adoption of the Ministerial Declaration for this HLPF, delegations began to pick apart its provisions, with one caveat after another directed towards language in the Declaration from which delegations maintained the right to distance themselves, some on sovereign policy grounds, others on grounds of culture. Especially troubling to me was the fact that this distancing was most often directed towards language on climate change and reproductive rights, areas of particular urgency for our young people as the planet continues to bake and women’s rights continue to lean in the wrong direction.

For us, despite another round of discouragement, these caveats must be understood as setbacks but not deal-breakers. If there is not sufficient urgency or inspiration in UN conference rooms, there is still space for us to supply it. If delegations try to “go small” in keeping with their instructions from capital, we can do our part to expand the frame, to keep the focus on areas of greatest threat, to reassure constituents that we will continue to apply an active and flexible lens to global problems which we know are unlikely to disappear unless we do.

We also recognize that the “cherry picking” around the operative paragraphs of the Ministerial Declaration is unlikely to reassure an anxious global public wondering if the many ministers and leaders of diplomatic missions gathered for this HLPF actually understand what is now at stake. Perhaps they’ve simply heard it all before, heard it so often in fact that there is no longer shock value, no longer anything to hear that can inspire anything more than tepid motions towards a “consensus” which is unlikely to motivate states not already “all in” on sustainable development to significantly shift their national priorities.

What we need to add to the mix is more inspiration, words and images that can move people, move them in ways that our “flat,” cautious and cliche-ridden policy language often cannot, move them to take up their rightful place in the world and affirm the life that can still be theirs.

Indeed, the most inspirational moment of the week might well not have been in the HLPF at all, but in the Security Council of all places where Colombian and UN officials convened to honor the release of the Final Report of the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Co-existence and Non-Repetition. The Declaration emerging from this report is most everything a document of this sort could be — smart and humble, informed and forward looking, generous and fair, tethered both to a complex national history and the spontaneity of its current moment, this and more in gorgeous, moving prose which seeks to vindicate the “blood of brothers” shed over and over by mapping out specific pathways allowing a weary nation to “go further until we love life.”

At the UN, it is now most often the president of the General Assembly who speaks in such tones. But he will leave his office soon and it is up to the rest of us to decide how to maintain that culture, a culture that inspires and assesses courageously, a culture that is not satisfied for one moment until the words on paper become hopeful change for the millions who long for it. For us and others the task is also to maintain flexible expectations in the face of the “unexpected sparks” of change, along with a posture which conveys that a sustainable peace still lies in our hands, especially so as we are able to resist the temptations to see only what we want to see or hurl pre-deteremined expectations at others from the sidelines.