The way things are supposed to work is that we’re supposed to know virtually everything about what they [the government] do: that’s why they’re called public servants. They’re supposed to know virtually nothing about what we do: that’s why we’re called private individuals. Glenn Greenwald

To claim the affection and to do the spying. It is something not wrong, but the danger. Ehsan Sehgal

Of course I’m not going to look through the keyhole. That’s something only servants do. I’m going to hide in the bay window. Penelope Farmer

Harry swore to himself not to meddle in things that weren’t his business from now on. He’d had it with sneaking around and spying. J.K. Rowling

On Friday afternoon, in the presence of Dr. John Burroughs of the Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy and Dr. Bonnie Jenkins – formerly the US National Threat Coordinator – we met with a group of our younger activists regarding threats to their future and what older folks like me need to do differently such that their stake in a future clouded by weapons, climate and other threats can be better magnified and encouraged.

We try to have these conversations on a regular basis, in part because of our deep respect for the people we are blessed to attract into our space, in part because the list of threats seems ever to be growing and shifting, and in part because few (in this work at least) offered us the same opportunities for sharing and disclosure way back when we were the younger ones.

I have often said, jokingly, that when I was younger, I spent most of my time catering to whims of older persons; now that I am older I spend a good bit of time catering to the whims of young persons. Perhaps it has always been so. Perhaps it must always be so. Indeed, one of the tests of character that we subtly employ here is the “test” of concern for generations to come, the recognition that those in their 20s and 30s are not, in fact, the last generation but merely the latest in a sequence to “come of age” with younger persons nipping at their heals, needing guidance from them now about how to navigate the treacherous spaces relentlessly unfolding in the global commons.

Part of this mentoring responsibility involves the courage to assess the risks coming into view and not only the ones that are widely known. We “know” about threats from nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. We “know” about threats from climate change and biodiversity loss, though we often organize our lives as though we don’t. We “know” that economic and social inequalities are still growing, though here in NY’s privileged spaces we tend to evaluate the success of our lives within narrow peer bandwidths, failing to appreciate the many advantages that have allowed us entry into the economic and policy “pods” we now jealously guard.

And we seem to assume (or wish) fervently that technology will somehow enable our collective rescue, that we will find the precise coding that will allow our machines to deflect incoming meteors, “eat” the carbon that is warming our atmosphere, skim the plastics off the surface of our dying oceans, and “blockchain” our way to more efficient and ethical means to link productive capacity and consumer demand.

And it might eventually be able do all of those things. But in the meantime, we are also guilty of enabling technology of a different sort, enabling it to essentially run amok beyond the control of government and multilateral institutions, making more and more decisions for us that, at both a personal and institutional level, we feel less and less able (and inclined) to resist. From self-driving cars and autonomous weapons to highly sophisticated surveillance that, more and more, relies on the phones that have become deeply embedded in our psychology as well as our logistics, we have largely abandoned scrutiny of a force that to some now seems as inevitable as our genetics and hormones.

The UN has not remained entirely aloof from these concerns. In a report recently released by the UN Conference on Trade and Development, the authors made clear that, for all their potential and realized benefits, global digital platforms tend to further “accentuate and consolidate” wealth and power rather than “reducing inequalities within and between countries.” Moreover, at a Mexico-sponsored “Youth Migration Film Forum” event this week, the highly moving films about the value and dignity of migrant youth were punctuated by cautious referrals to the high-tech surveillance on both sides of the US-Mexico border that mostly reinforces caricatures of migrants as disembodied threats rather than as human beings with families, aspirations, skills and faith.

And during a session of the UN General Assembly Third Committee, the ever-thoughtful Philip Alston gave his final report as the UN Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty, during which he spoke about the ways in which technology is now insulating and intimidating rather than liberating persons living in poverty. He spoke passionately about the largely “human rights-free zone” characteristic of much big technology, the degree to which surveillance of the poor (and the rest of us) is being used by the governance and investment classes to “punish” persons who use “our” money for purposes that the authorities don’t approve of. As he (sadly for us) ends his mandate, Alston urged creation of a “shared language of human rights” that can help us avoid the collective (and very real) danger of “stumbling zombie-like into a “digital welfare dystopia” where decisions about human beings are based on algorithms rather than relationships, on the need to control rather than the need to assist. Indeed, in a world where many people trust their phones more than their neighbors, this “dystopia” warning is not as far-fetched as it might initially appear. Our interns certainly took it very seriously.

Part of the solution clearly lies in technological oversight, in resurrecting the role of the state to protect people from excessive interference from the technologists – and from the governments themselves. Clearly, the “surveillance culture” of our time has impacts, not only for migrants and the poor, but for others who seek to defend their rights and interests, to any effort to reaffirm the importance of public spaces and values not subject to private priorities. Much time at the UN now, including this week, is properly devoted to increasing attacks on civil society, activists or journalists, anyone who dares to defy “the norm.” But in too many instances, under-regulated state interests and private-sector technologies are aligned in a desire to shrink and securitize public spaces. Even UN spaces.

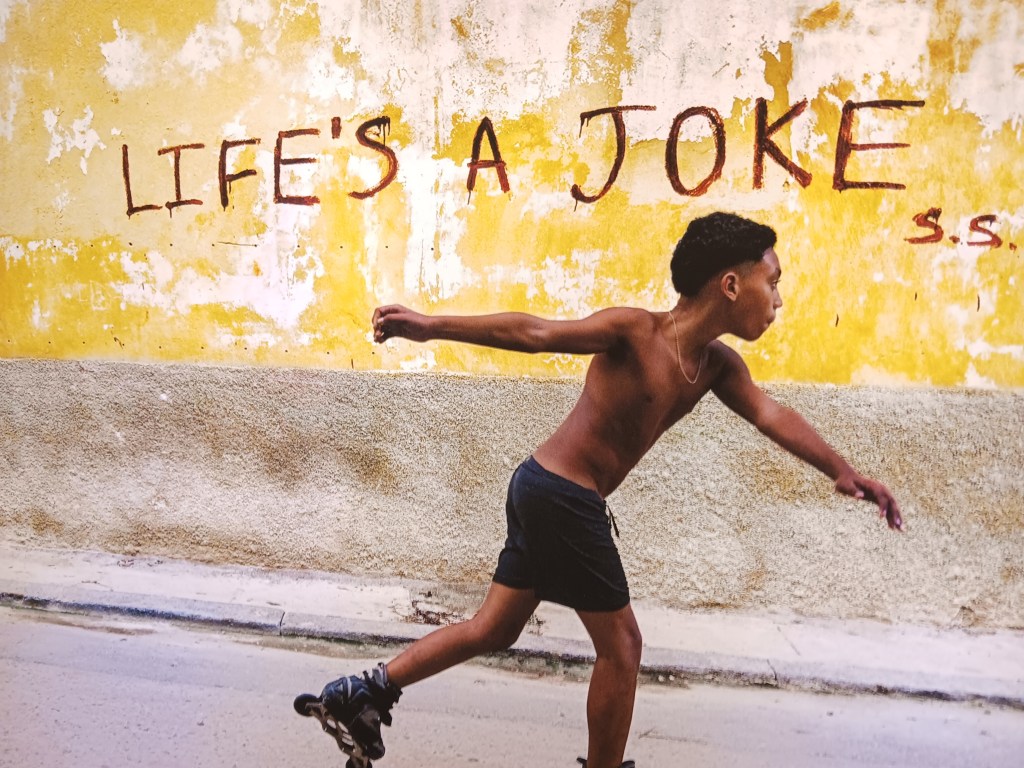

At another event at the UN this past week on “public space in a digital age,” UN-HABITAT brought together a variety of experts who critiqued “sanitized, securitized” and highly expensive development priorities such as NYC’s “Hudson Yards.” Such priorities often lead to the neglect of public spaces more conducive to personal engagement, spaces that can help people connect to each other and inject dimensions of “playfulness and plurality” into communities in ways that enable and enhance both personal connection and the “emotional health that we in this city (and in so many others) badly need.

This session was full of insight, much of which was directly relevant to this post: the suggestion that “citizens are not aware of how social media now allows private actors to create, define and surveil public space,” the degree to which digital space encourages narrow mindedness while public space tends to cultivate “broad mindedness,” and the sense that in healthy environments, personal relationships must take sequential precedence over their digital counterparts. Amazon, one speaker half-joked, “wants us to live our entire lives in our pajamas,” engaging the digital realm as consumers of goods and gossip while eschewing the risks associated with that “playfulness and plurality” which only public spaces can deliver.

I can only speak for myself here, but I don’t want a life without risk, nor do I want a life dominated by technology over which I have no control, one which offers me products I don’t want and promises to “save” me from “threats” that, to my mind at least, are less threatening than the steady erosion of personal freedom, respect for diverse voices, and some semblance of privacy. I would also much rather sit in a Bronx park watching children play than walk the High Line with tourists and their selfie-sticks.

As one of the youth delegates at the “Migration Film Forum” rightly noted, technology can in fact create new contexts for inclusion. But this is mostly true when we sequence it properly, when technology becomes merely the means to extend connection, not give it birth. We may be collectively too addicted now to our devices, too willing to forgive them for digitalizing our complex life preferences, keeping us in our sleeping clothes, and spying on every idea and action our lives are capable of generating.

But unless we can find the courage to resist and reshape that addiction, to re-personalize the spaces and relationships that are now, too-often, providing little more than digital fuel for Alston’s “dystopia,” this self-inflicted “pajama party” is not going to end well. We cannot go on “claiming affection” while spying on each other, judging each other by what we find in some random database rather than what we know from our own direct engagements.

The lesson here seems clear: when we cease to trust our own senses and experiences, we risk losing a good chunk of our remaining capacity to trust one another. There is, perhaps, no risk facing the global commons greater than this.

Tags: migration, public space, sustainability, technology