Do not call the forest that shelters you a jungle. Ghana

There is no medicine to cure hatred. Ghana

The teeth are smiling but is the heart? DR Congo

A fool looks for dung where the cow never browsed. Ethiopia

One who conceals their disease cannot expect to be cured. Ethiopia

One who continually laments is not heeded. Cote d’Ivoire

Seeing is different from being told. Cote d’Ivoire

Evil knows where evil sleeps. Niger

Fine words do not produce food. Nigeria

The heart is not a knee that can be bent. Senegal

One who upsets a thing should know how to rearrange it. Sierra Leone

A roaring lion kills no game. Uganda

Those of you who continue to read these missives know that the quotations at the head of the posts are often as impactful as the prose which follows. These quotations mean much to me and often to the readers as well. The ability to capture important human lessons in a sentence or two, to be suggestive without taking on the burden of being definitive, to leave people with things to ponder as well as ways to grow, this is to my mind a considerable gift.

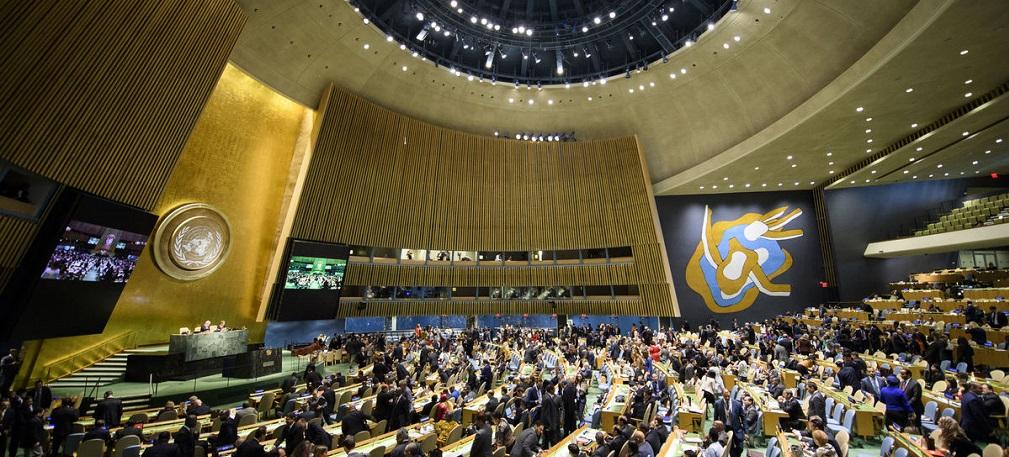

We who ply our wares in the halls of policy, with few exceptions, do not search hard enough for the images that can stimulate thought and growth beyond their initial utterance. We use so many words – so many — words which are too-often redundant, repetitive and entirely metaphor-phobic, words often spoken as though we were merely reciting lessons handed down to us in some secondary school, words which may fulfill the “assignment” given to us by our superiors but offer little in the way of inspiration or takeaways, conveying little reason for others to hope or care. Indeed, inside the UN as with other large institutions, there is little reason to believe that any of our “fine words” will survive the end of the meetings in which they are uttered, if indeed anyone much was listening in the first instance.

We are all constrained by our habits of thought and communication, it seems, and this surely applies to the language of diplomats and those of us on their margins who have internalized the culture of the UN and perhaps misplaced the reality that too many of our alleged constituents have largely tuned us out. The world remains conceptually-speaking largely absent from our policy bubbles, not because there is an absence of truth in those bubbles but because the conveying of that truth is so often deficient in urgency, in potency, indeed in poetry. Even during what could be construed as potentially profound UN events – last week’s successful General Assembly discussion and resolution on the “right to a healthy environment” and this week’s NPT Review Conference (nuclear weapons) the language used to convey concern is overly constrained by time in part but also by temperament. We rush through presentations on important issues as though we have a train to catch. We speak in the tones to which we are authorized, tones which rarely convey or capture the deep anxieties and misgivings of diplomats, but also of a global public now attempting to cope with a wider range of emergencies than they ever would have imagined.

Thus the decision was made some time ago to balance our own narrative of global events with some profound utterances from other times and through other mediums. So far as I can tell, the only downside of this decision has to do with their sources, likely from too many men and too often emanating only from western cultural contexts as well. That the quotations in the posts are still more likely to motivate and inspire than any of the “clever by half” prose that generally follows is, to my mind at least, an indication of how much we long for rhetoric which is more compelling than hard concepts gleaned from hard data, more than recitations about the “importance” of institutions and their policy products which have not done nearly enough to inspire our trust or confidence, more than concepts that pull us out of the contexts which still have much to teach if we would only pay more attention to sources of local wisdom and just a bit less to its relentless alternatives courtesy of major policy centers, corporate media outlets, university-based think tanks and published reports emanating from our global institutions.

Such alternatives have literally conquered the conceptual landscape in all but the most remote communities while demonstrating a limited ability (as have we all) to solve problems which now threaten our future as a species. And thus we’re trying something different today, quotations not from literature and philosophy, not from the recognizable figures in our own fractured western history, but from proverbs; stories and images which people in diverse cultures have long used to communicate truths that, given the difficult and/or complex logistics which define so many of our lives, we have overlooked or forgotten altogether. The underlying lesson of all these proverbs is that clues to a better life, to better communities, are at least as much in the seeing as in the telling. The best proverbs take their material from the life around them, life that is available to all if not availed by all, life that has its own lessons to convey beyond rhetoric and textbooks, life calling on us to pay more attention to the insights knocking at our doors, to use all of our senses, to look for and share gifts of insight which can help us exercise caution where such is the more sensible path, and take a deep breath and push forward when more courageous action is warranted.

One of the limitations in the deployment of the proverbs above is my own inability to designate authorship beyond the nation-state. The best proverbs, of course, have impact across cultural and even national borders. But we also know that, in African and other global contexts, such borders are functions more of colonial convenience than local assent. That the proverbs listed here mostly do not have a more specific cultural reference point underscores my own limitations. Thankfully the lessons embodied in these and other kernels of insight have relevance across cultural divides as they have relevance beyond the limitations of the English in which they are here communicated.

But despite this, it is also the case that we now live in a world dominated far more by fact-checkers than storytellers, a world in which the data sets of our times are as likely to drive us to despair as to trust and confidence, drive us towards indifference rather than engagement, drive us to see if we can “wait this one out” rather than participate in remediation with the energy and wisdom still at our disposal.

On top of this, we also inhabit a time where many are championing their own truths in response to what has become a veritable sea of disinformation undermining confidence in any and all institutions and individuals who seek to do their homework and “play it straight” with what they know. We forget that while truth is not subjective as so many now seem to claim, it is always partial, valuable in the contexts in which it appears but not in all contexts, not in all circumstances, at least not in the same manner.

I would suggest that our erstwhile preoccupation with “truth” grounded in an endless series of verifiable “facts” has not reduced lying – to ourselves and others – even while the cameras are rolling. We have cultivated an extraordinary ability to accumulate masses of “facts” assembled to create arguments to justify ideas and behaviors which are barely, if at all, justifiable. Even in global institutions such as the UN, complex arguments leading to one-sided critiques or inflexible assertions of “national interest” have become more and more the coin of the realm. Acknowledgements of wrongdoing are almost non-existent. Direct apologies are even rarer. Clarifications of position are occasionally offered, but little is conveyed indicating that positions have been significantly rethought or revised based on fresh experiences or circumstances. We give lip service to the wonders of science as well as to the need to reach constituents “where they are.” But the language of bureaucracy is rarely the language of community or culture, and our dominant syntax remains generally too conceptually complex, too “flat” in its application, too-often lacking in thought-provoking affect to inspire the local consent and revitalized initiative upon which the successful pursuit of something truly important like a “right to a healthy environment” ultimately rests.

We need softer landing spots for the accumulation and transmission of human wisdom. The proverbs listed above and innumerable others of their kind from all corners of the world offer (at least to my mind) a more straightforward, if also incomplete, path to wisdom from a range of sources and from which the rest of us have become too-often detached. Indeed, a “roaring lion kills no game.” Indeed, “one who conceals a disease cannot expect to be cured.” Indeed, “one who continually laments is not heeded.” Indeed, “fine words do not produce food.” Indeed, “there is no medicine to cure hatred.” On and on, kernels of truth which instruct and provoke, which take what has been seen and convert it into words and images that can connect and inspire.

Whether in this form or other, we in policy-land need to find more of those simpler and wiser forms of discourse which can stretch our experience, which can make our hearts smile as well as our teeth, and which can forge stronger and more urgent links between the world we are trying to build, the constituents we are trying to reach, and the people we need to become.