To handle yourself, use your head; to handle others, use your heart. Eleanor Roosevelt

Our chief want is someone who will inspire us to be what we know we could be. Ralph Waldo Emerson

Keep your fears to yourself but share your courage with others. Robert Louis Stevenson

You will see a great chasm. Jump. It is not as wide as you think. Joseph Campbell

Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing. Albert Schweitzer

If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more and become more, you are a leader. John Quincy Adams

Leadership is not about a title or a designation. It’s about impact, influence, and inspiration. Robin Sharma.

Last week under the presidency of Slovenia, the UN Security Council held a debate on the topic “Leadership for Peace.”

Needless to say I was intrigued though recognizing that these terms connected by “and” are not straightforward; indeed they often cover up more light than they reveal.

Peace is ostensibly what Global Action was created to promote and inspire. Our track record over 20+ years is mixed to be sure. We haven’t sufficiently inspired people to transcend their own anger and grievance, nor governments to honor their political agreements and commitments; nor groups like ours to self-reflect on how endless fundraising compromises integrity and effectiveness. Peace, after all, is something we do as much as something we promote. As Albert Schweitzer intimated above, we have done a better job of advocating for peace than setting a peaceful example, forgetting at times that any success in our chosen realm requires an intentional, thoughtful blending of both.

And what of leadership? For many of the delegations present in the Council chamber, the issues which consumed their interest were related to whom the next Secretary-General might be after Antonio Guterres’ two terms in office. This is not an irrelevant consideration given the current state of the UN and given the complex role that the SG plays in that space; a role as many others have noted, more “secretary” than “general, more implementer of the wishes of the large and powerful states than enforcer of the UN Charter and international law. The current SG has a bit of “chicken little” in him, constantly pointing out the ways in which international law and the basic rights of civilians have been trampled, climate change threats have largely been ignored, and conflicts continue to rage under the umbrella of large power interests and in clear violation of the UN Charter. He has surely been in a tough spot. Nevertheless, pleading for change and constructing a system which can inspire, make and sustain change are not synonymous. The next SG must do some of both but the latter tasks constitute a higher bar.

I am in the process of writing a longer piece on leadership as a contribution to a project which we will help unveil in Kosice, Slovakia in February, a project tentatively entitled the Carpathian Leadership Fellows Program and currently being facilitated by our board members Dr. Robert Thomas. The project will focus on various aspects and incarnations of leadership pertinent to Ukraine and surrounding areas, organized around key questions including, What does leadership entail for post-conflict Ukraine? What does it require for the various stakeholders – teachers, engineers, clergy, architects, police, merchants, artists, farmers, health workers and more – who will be asked to play prominent roles in helping Ukraine and the region recover from damaged and aging infrastructure, from young people whose education and hope for the future have both been compromised, from people internally and externally displaced by violence waiting more and less patiently to return to their communities?

I will briefly share aspects of this project (and this season) which are of particular importance to me – some relevant to the UN and others more directly relevant to the baby in the manger which is our one and only Christmas point of origin.

On leadership, what the UN cannot easily accommodate, indeed most bureaucracies cannot, is leadership’s organic nature. Quotation after quotation at this stage of my investigation highlights this aspect of leadership, organic in the sense that it is intimately related to the active consent of those being led and is entirely related to context and condition, requiring administrative skill but also the inspiration that comes from the heart and connects to the heart. The testimony I have found reflects leadership which inspires us to jump over chasms which seem too daunting; leadership which insists that there is a better part of ourselves yet to be revealed to self and others; leadership which not only knows what needs to be done but also who needs to do it and how to inspire the energy, trust and perseverance to rebuild schools and communities, hospitals and transportation; leadership which makes hope more tangible especially for people whose need to believe again in the hope of a better world, hope which has too long been buried under rubble of various forms and not of their own making.

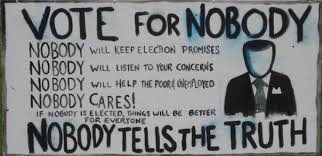

At the UN, leadership claimed is undermined by several factors including the machinations of the large global powers, the disconnect between policymakers and constituencies, but especially by the promises which we make through that policy, promises which elevate many more expectations than they satisfy, promises unkept which damage the trust needed for our leadership, such as it is, to inspire broader-based action for the more peaceful, just and prosperous world we claim to want, for our children and grandchildren if not for ourselves.

And this leads me back to the Christmas manger and the inspiration of a child. There is a lovely and oft-quoted passage from the Talmud, shared by sages as remarkable as Martin Buber and Abraham Joshua Heschel, that with the birth of each child, “the world begins anew.” Indeed, with each child the hope of the world is restored in measures small and large. Leadership of course should also be about instilling and growing that hope, helping people find a reason to believe that their lives and labors matter beyond fiscal outcomes. In this way, leadership can reinforce what I understand to be a Christmas call to reach beyond the confines of what we imagine ourselves to be, to demonstrate skill and courage in larger measure in whatever contexts and conditions we find ourselves.

For me and for many others, it is the child in the manger, the child of meager circumstance and divine significance, who remains my foundational source of hope especially through what for us has been a long season dark and cold in aspects far beyond climate. For me, this incarnation of hopefulness lies well beyond the province of officialdom and bureaucracy. It points us towards what we often long for but also find elusive, the power and grace to be more than we are now for the people who need our example as they seek to call out more from themselves as well. These bonds of influence and inspiration now seem to be in serious need of repair. The promise and power of Christmas make such repair well within our remit.

Blessings to all in this season,

Bob