If the government is big enough to give you everything you want, it is big enough to take away everything you have. Gerald R. Ford

I don’t make jokes. I just watch the government and report the facts. Will Rogers

If your dreams do not scare you, they are not big enough. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

This past week, we were privileged to welcome Ms. Thalassa Cox from the office of the Solicitor-General of St. Lucia. Thalassa has come to explore the UN, but also to learn what we are hopefully well-suited to teach – what the UN can and cannot do well, and how best a small state government can participate in (and in turn influence) global policy in this highly-complex and often self-referential institution.

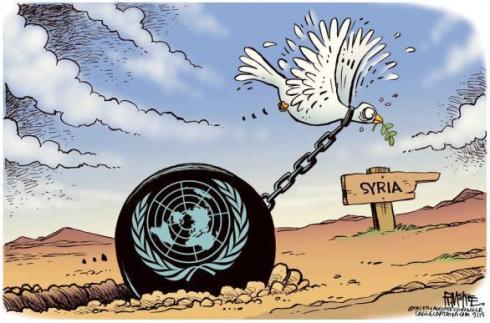

And what a week it was for her to come. The Security Council took on South Sudan, Syria and especially North Korea, in the latter instance drawing an oval punctuated with Foreign Ministers, some of whom (especially the US) seemingly determined to “act” instead of talk, but without a plan for managing the (perhaps dire) consequences that an as-yet-undetermined plan of action might itself create. At the same time, the General Assembly was deeply engaged in its own revitalization, including its sponsorship of major upcoming discussions focused on human migration and the health of our oceans. The Peacebuilding Commission endorsed a peacebuilding plan for Liberia that can serve as a model for other states emerging from conflict. The Committee on Information met to review how the UN tells its story and in which languages it chooses to tell it. And the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues brought splashes of color and moral resolve to the UN, including the presence of women in tribal costume holding their babies, reminders both of our collective, gendered responsibility to “First Nations” and, in the case of the babies, of precisely on whose behalf we do our policy work.

After years in this multilateral space, I am convinced that a more regular presence of persons representing different human abilities and cultural contexts — and their babies — would help us make better policy, and become better people as well. People wearing headdresses or in wheelchairs, people walking with guide dogs or facing unique forms of discrimination; these and more come from families and communities with their own dreams, some of which can occasionally find expression at the UN, but others of which are even larger and more poignant than what we can routinely appreciate in this space.

Also this week, in a mid-sized conference room and under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council, the Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA) met in session to explore, among other matters, the role of local governance in the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While we have covered a bit of CEPA in past years, we were gratefully present for more of the discussion this year, in large part due to Thalassa’s enthusiasm for the learning which the diverse CEPA experts were well-suited to provide.

As we have mentioned often in this forum, the SDGs represent a promise that we have made to the economically poor, the politically marginal and even to generations yet to come; a promise to define and implement a plan to level the social, political and economic playing fields, to eradicate persistent poverty, to empower women and cultural minorities to kick open doors to participation, to remove the dangerous masses of plastics and other toxins poisoning our oceans, to preserve our dwindling biodiversity and fresh water access, and to create structures of sustainable production and consumption that can help reverse climate change and create desperately needed jobs for youth and families.

This grand promise holds direct and compelling implications for peace and security. In our view, if we can collectively make our “best faith” effort on the SDGs, our chances of “sustaining peace” will improve dramatically. But if our effort falls short of “best” then the crises that now overwhelm our existing peace and security architecture will only grow in numbers and complexity. Moreover, and given our stubborn reliance on ever-more-sophisticated military arsenals, what is left of our credibility on conflict prevention and peace will likely have eroded as well. Serial promise breakers are generally not highly sought after as conflict mediators.

We and our office colleagues often ask what else is needed if the promises of the SDGs are to find a satisfactory fulfillment. The UN is working hard on appropriate stakeholder arrangements, on predictable funding (including increased and corruption-free domestic revenue), on comprehensive data and robust technology transfers. All of this is necessary, though none by itself is sufficient.

What else is missing? Some clues were offered by CEPA itself, which included the quite sensible notion that, as important as global norms can be, the promises embedded in the SDGs must attract large numbers of local champions if they are to succeed. Such “champions” can provide context-specific remedies for habitats in need of restoration, lifestyles that need to be healthier, economies that can better respond to local consumer needs, schools that promote knowledge of hometowns and not only of other towns – even government officials who can back commitments to “open, inclusive” governance with specific measures to protect media and information freedom, promote access to justice, and guarantee fair and competent government services.

As the Moroccan expert in CEPA made clear, there is a need to “decentralize” our approach to the SDGs, not so much because the largest structures of global finance and multilateral governance are deemed serially indifferent, but because constituents in real danger of being “left behind” by behemoth institutions can more easily be identified and their development needs addressed through responsive local structures. In addition, from our own vantage point, such decentralization points the way to perhaps the most essential and largely missing ingredient in SDG implementation; the willingness of people worldwide, in areas rural and urban – including right here at the UN – to “up our game” in response both to immediate crises “created on our watch” and to warnings of disasters that would, if not prevented, weigh so very heavily on the skills, resources and dreams of future generations.

Local government can and does have its own limitations regarding accountability to the public and its financial obligations, as well as to genuine openness and fairness. As obsessed as we sometimes are by globally-impacting events emanating from places like Washington and Beijing, there is plenty to watch and report on at local levels as well, some of it equally frightening and/or even at times a bit humorous. But fear and laughter aside, unless we can improve at local levels standards of government transparency and inclusive service delivery; unless we can enable citizen-centered governance where people have a role to play and not just a complaint to lodge; unless we are willing to defer to local testimony regarding who actually remains “left behind;” then the SDGs will remain an elusive promise at best. And the conflict potential emanating from a damaged planet and its chronically disappointed people will continue to grow.

In the often “nomadic” world of global diplomacy it is relatively easy to lose sight of local rhythms, those that promise social progress and others that impede it. Despite the relatively small audience for its UN deliberations, CEPA is helping pave the way for closer and more effective SDG interactions among all levels of government, while continuing to insist that efforts at local level to eradicate poverty and fulfill other SDGs offer the most direct, most personal “diagnoses.” Moreover, as CEPA certainly recognizes, local initiatives are best suited to encourage and unlock opportunities for people from diverse cultures and with wide-ranging capacities to contribute directly to the fulfillment of a large and complex SDG promise, a hopeful dream for a better world that we simply cannot afford to ignore.